In this blog I am looking into Key

Performance Indicators or KPIs. Often I see companies tracking and

reporting lots of KPIs only to find that they are only measuring

those things that are easy to measure and not measuring the things

that really matter. My advice is to reduce the number of KPIs that

you track, and only track those that will tell you how your business

is really performing, but accept that these will be harder to define

and measure.

In order to understand what's going on

in your business you need to define, measure and track Key

Performance Indicators (KPIs). A good set of KPIs will enable you to

understand if your business is meeting the targets that you have set

and all is well, or whether you are off track and need to take

corrective action.

It is easy to draw analogies. A captain

in charge of a ship needs to know his position and course as well as

the fuel and other supplies that he has on board in order to know that

he will reach his destination on time. At an annual check up your

doctor may measure your heart rate, height and weight to check that

you are healthy. He may also take a blood sample to measure useful

KPIs in your blood like cholesterol, glucose level and so on. Both

the ship's captain and the doctor are looking for irregularities in

the KPIs. If they are out of tolerance they will probably monitor

them more closely, investigate the root cause and take corrective

action to bring the KPIs back within tolerance.

How it should work

It's exactly the same for businesses,

and ideally you will have a hierarchy of KPIs that all link together

in a coherent pyramid. At the highest level you will be tracking

things like gross margin, Net Profit, Days Sales Outstanding,

Customer loyalty and so on. These should be aligned with the stated

goals of your business as agreed with shareholders. During the yearly

cycle these KPIs will show whether you are on target to meet your

objectives for the year or whether corrective action needs to be

taken.

At lower levels, though, your

organisation will be be divided into business units, functions, teams

and so on. Each of these groups will have objectives defined, which

if met should make the necessary contribution to the whole. They will

also be required to report the detailed figures that feed into higher

level KPIs.

In an ideal world, the pyramid of objectives and measures is completely aligned. The highest level objectives break down all the way to individual performance measures for each employee and supplier and if everyone meets their targets, the business as a whole meets it's target. If anything is going wrong, then drilling down will enable you to quickly pinpoint where exactly the problem is so that you can take corrective action.

How it usually works

In practice this seldom, if ever,

happens. Defining such a pyramid of objectives and measures is a huge

task and the world changes. On the one hand, it is human nature for us to isolate those

things that we can control, especially if we are being measured on

them. So a manager will want to define his KPIs based on his

department's performance isolated from the rest of the business. On

the other hand it can be complex and expensive to gather and process

all the necessary data. Objectives change from year to year, and there simply isn't enough time to build the perfect pyramid of KPIs for them to be useful in any meaningful sense. The pressure to find shortcuts is enormous,

and the question often asked is “what data do we already have that

will tell us more or less what we need to know?”

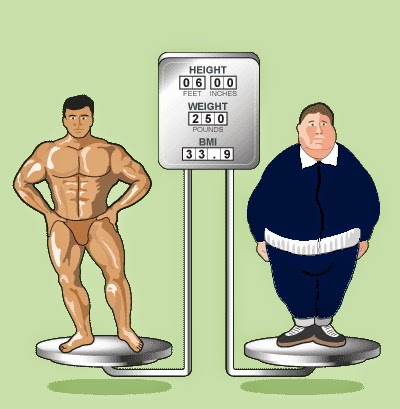

For an example, let's return to our

doctor and the annual check up. A widely used KPI is the Body Mass

Index or BMI. This is easy to define and measure. It is simply your

weight (in kg) divided by the square of your height (in m). In my

case I weigh 78kg and I'm 1.73m tall, so my BMI is 26.0 which makes

me overweight, so I should take corrective action. I should aim for

75kg or less . Although it is simple, the BMI has come in for some

well deserved criticism, because it doesn't always tell you what you

need to know to establish if someone is overweight, underweight or

just right. Since muscle is heavier than fat, athletes often have high BMIs. Methods for accurately measuring body fat

include calipers, electrical resistance or a full body X-ray scan.

BMI is an easy KPI to measure, but is not always useful

It's the same with the KPIs in your

business. Many of them have been defined not because they give you an

accurate measure of the health of your business, but because they are

easy to measure and are related to the things that you want to know.

A good example that many businesses measure is headcount. This is

easy to measure, and if combined with payroll data it's easy to turn

into money terms. So teams, departments and so on are set objectives

in terms of staff numbers or staff costs. It's easy to measure and

also relatively easy to control. As a result these objectives are met

in most companies. Next to this, a team or a department will often be

set a target in terms of output. By combining the two, you get an

idea of productivity in terms of output per unit cost. The chances

are though, that the output is defined based on what's easy to

measure and not what's important. Just because a team or department is meeting their targets, it doesn't necessarily mean that they are adding value to the business.

How poorly defined KPIs can encourage a

silo mentality

Consider the following scenario. A

retail insurance company consists of a sales and marketing

department, a claims department and a call centre that serves as the

first line for both.

The sales and marketing department has a fixed budget for the year and a target for new contracts. For simplicity all calls to the call centre that are logged as “new contract” are counted towards this target. The claims department has a fixed budget for the year and a target for processing claims within a given timeframe.

The call centre also has a fixed budget and a target of average handling time for inbound calls.

Based on experience, the sales and

marketing department have determined that the most cost efficient way

of generating leads is to launch a small number of high profile

campaigns, so plan 4 saturation campaigns spaced over the year. The

call centre manager meanwhile calculates that the most cost effective

way of staffing her call centre is to keep the headcount level and

avoid overtime as much as possible. She knows from experience that

she can manage the peaks by telling customers that they will be

called back later if the call centre is busy. This even helps boost

her average handling time KPI because both the initial call and the

callback are counted, so what could have been a single call is now

counted twice, and the average handling time is halved. What she

cannot afford to do is to authorise overtime or hire in temporary

staff to handle the peaks. That just increases her staff costs, and

leaves her overstaffed during the quiet periods (and when it's quiet

her agents spend longer with each customer, so the average handling

time goes up).

So, what happens when the sales and marketing launch a saturation campaign? New customers suddenly start ringing in asking to sign up or wanting more information. The call centre can't cope and so does the bare minimum by logging the call and promising to call back later. They keep their KPIs under control. Critically each call is logged as a sales call, which feeds into the sales and marketing KPI, so they also meet their targets. What happens though when the customers are called back? Do they still want the insurance policy now that they know that the call centre hasn't got time for their call? Are they actually too busy right now doing something else, after all they originally called at a time that suited them? Have they checked out the competition and chosen their product? Whatever happens, some of them who would have signed up for the policy, now won't.

The point here is that each group is

hitting their targets, and can cite their KPIs to prove

it. It is clear though, that this company could perform better.

Objectives and KPIs could also be defined that are more relevant and

which encourage and reward better behaviour. For the sales and

marketing department, they should be aiming at total number of new

signed contracts. It's not the call that counts, but the signed

contract. The call centre shouldn't be measured on average handling

time, but on the notion of “first time resolution” i.e. did they

successfully respond to the customer's request in a single call.

When you start defining KPIs like this,

though, things start to become more complicated. Firstly the

definition becomes more complicated as does the means of measuring

it. Instead of just counting call logs you need to count new

contracts, and then distinguish between new contracts and extensions,

but what if a customer upgrades their contract, does that count as a

sale or not? Defining first time resolution is also not easy. How do

you distinguish between a customer who calls twice because the

initial enquiry was not adequately dealt with and a customer who

calls again for an unrelated matter?

Things also start to get more complicated because managers are forced to recognise their interdependencies. If the sales and marketing manager is now measured on converted contracts, then he is dependent on the call centre manager for ensuring that the calls generated by his TV advertising campaign are converted into signed contracts by the call centre. The call centre manager is also dependent on the sales and marketing manager because her team will be swamped if there is a blanket marketing campaign that generates large numbers of calls. A peak of calls will result in a dip in first contact resolution or an increase in headcount. This is a good complication, because it is clearly true. These two managers and their respective teams are interdependent, and if they are both to succeed, then they need to talk to each other and work out a plan where they both win. Well defined KPIs should encourage these discussions.

How to define intelligent KPIs

First of all, start with the assumption

that the KPIs that you currently have are probably sub-optimal, that

they are based on what's easy to measure rather than what's important

to measure and that they are encouraging departments and teams to

work in silos rather than to cooperate. However, for now, they are

the best you have, so don't throw them away until you have something

better.

Before going any further take a good

look at your business and understand what really drives it. What

drives your revenues, what drives your costs and what are your most

important risks? What drives your competitive advantage and how

important are customer loyalty or fraud to you? What are the factors

that you can't control or which are the same for all competitors in

your market? (If it's the same for everyone, there's no need to worry

about it.)

Once you have an understanding of the

most important drivers, define a small number of KPIs that

meaningfully represent these. Recognise that they will not tell you

everything, but they will tell you the most important things. They

will probably not be easy to measure, and neither will they align

closely with your organisational boundaries. For both of these

reasons, the discussions that you need to have will be difficult, but

having those discussions is a valuable process in its own right –

those discussions help to break down the silos and expose the

inter-dependencies. Once you have defined these KPIs, then implement

them. The data may be hard to find, or the processing to turn raw

data into meaningful measures may be complex – that's one reason

why you should limit the number of KPIs. Once you start measuring

them, reporting on them and managing against them, you will discover

new complications. Be prepared for some degree of iteration before

the definitions and the targets stabilise.

No comments:

Post a Comment